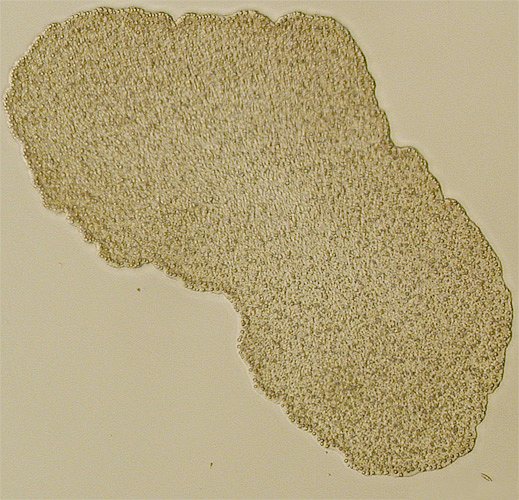

Trichoplax adhaerens is a bizarre little animal with a decidedly simple morphology. (You can see some here). There has been some question as to the relationship between this critter and other animal groups, but mitochondrial sequences (Dellaporta et al. 2006) and, as of this week, a complete nuclear genome sequence (Srivastava et al. 2008), suggest that it is a modern representative of the earliest branch to split from the rest of the animal lineages (for more detail, check out John Timmer’s discussion). The term “basal” is usually applied to lineages like this, often with the assumption that basal means primitive. Sometimes genome sequencing articles exhibit misunderstanding of what “early branching” actually means, but I must give kudos to Srivastava et al. (2008) for their refreshingly apt conclusions:

Trichoplax‘s apparent genomic primitiveness, however, is separate from the question of whether placozoan morphology or life history is a relict of the eumetazoan ancestor. For example, the flat form and gutless feeding could be a ‘primitive’ ancestral feature, with the cnidarian–bilaterian gut arising secondarily by the invention of a developmental process for producing an internal body cavity (as in Bütschli’s ‘plakula’ theory), or it could be a ‘derived’, uniquely placozoan feature that resulted from the loss of an ancestral eumetazoan gut. Unfortunately, the genome sequence alone cannot answer these questions, but it does provide a platform for further studies.