There are many good science writers and press officers around. This post is not for them, as they will certainly reject all of its key points. Nor is it for the members of the media who are already adept at producing sensationalistic, inaccurate, or downright ridiculous science news stories. This post is for those writers somewhere in the middle who sometimes get it wrong but can’t quite master the art of atrocious science reporting.

Here, then, is a concise guide for how to write really bad science stories.

1. Choose your subject matter to be as amenable to sensationalism as possible.

Some scientific studies may be considered elegant and important by scientists, but if they help to confirm previous thinking or provide only incremental advances in understanding, they are not newsworthy. What you need is something that will generate an emotional rather than intellectual response in the reader.

(If you’re stuck on this step, try coming up with a topic that fits into Science After Sunclipse‘s handy list of categories for science stories.)

2. Use a catchy headline, especially if it will undermine the story’s credibility.

The headline is what draws the reader in, and it is very important that this be as catchy and misleading as possible. Try to focus on outrageous claims. “Such-and-such theory overthrown by this-and-that discovery” is a good template. If possible, have an editor who has not read the story or knows very little about the topic come up with a headline for you.

3. Overstate the significance and novelty of the work.

Do your best to overstate the importance of the new discovery being reported. This is especially relevant if you are writing a press release at a university or other large research institution. The discovery must, at the very least, be described as “surprising”, but “revolutionary” is vastly more effective. Indeed, the reader should wonder what, if anything, those idiot scientists were doing before this new research was conducted (see step 4). Avoid implying that there is a larger research program underway in the field or that the new discovery fits well with ideas that may be decades old. Also, if the discovery — no matter what it is — can be linked, however tenuously, to curing some human ailment, so much the better.

(For writers reporting about genomics: if your story is outrageous enough, you may be eligible for an Overselling Genomics Award; note, however, that competition for this distinction is intense).

4. Distort the history of the field and oversimplify the views of scientists.

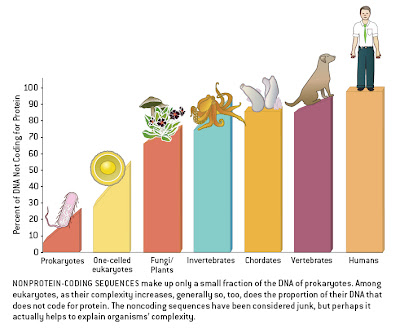

Whenever possible, characterize the history of the field in which the discovery took place as simplistic and linear. It is very important that previous opinion in the field be seen as both monotonic and opposed to the new discovery. If there are signs that researchers have held a diversity of views, some of which are fully in line with the new finding, this will undermine your attempt to oversell the significance of the study (see step 3). For this, there are few better examples than recent work on so-called “junk DNA“. Here, authors of news stories have managed to convince readers that “junk” was unilaterally assumed to mean biologically irrelevant, and that it is only in the face of new discoveries that stubborn scientists are being pushed to reconsider their opinions. The fact that both of these are utter nonsense shows how effective this approach can be.

5. Remember that controversy sells, and everyone loves an underdog.

If the results of a new study do not contradict some long-held assumption or incite disagreement among scientists, then readers will have little interest. As a consequence, it is important to characterize science as a process of continual revolutions (see steps 3 and 4) rather than one of continuous improvement of understanding. Refinement and expansion of existing ideas should not be implied. If there is no real controversy, invent one. And, whenever possible, set it up as a “David vs. Goliath” conflict between an intrepid scientist and the stuffy establishment.

6. Use buzzwords and clichés whenever possible.

It doesn’t matter if the words are used inappropriately or appeal to common misconceptions (see step 7), if it is catchy or well known, use it and use it often. This is particularly important if you would otherwise have to introduce readers to accurate terminology and novel concepts. “Genome sequencing” should be dubbed “cracking the code” or “decoding the blueprint” or “mapping the genome”, for example, even though these clichés are quite inaccurate.

7. Appeal to common misconceptions, and substitute your own opinions and misunderstandings for the views of the scientific community.

It is important that readers’ misconceptions not be challenged when reading a news story. In fact, the more a report can reinforce misunderstandings of basic scientific principles, the better. This can be combined with step 6 to good effect. It is also helpful to insert your own views and misunderstandings as though they were those of the scientific community at large. For example, if you find something confusing, mysterious, or (un)desirable, assume that the scientific community as a whole shares your view.

8. Seek balance, particularly where none is warranted.

A primary tenet of journalism is that it present a balanced view of the story and not make any subjective judgments. The fact that the scientific community has semi-objective methods for determining the reliability of claims (such as peer review and the requirement of repeatably demonstrable evidence) should not impinge on this. It is therefore important to present “both sides” of every story, even if one side lacks any empirical support and is populated only by a tiny minority of scientists (or better yet, denialists and cranks). This does not necessary conflict with step 5, because a false controversy can be set up using an appeal to balance. For example, a productive strategy is to provide one quote from someone at the periphery of the field and one quote from a recognized expert to make it seem as though there is debate about an issue within the scientific community. Under no cricumstances should you explain why the scientific community does not accept the views of the non-expert. This has proven very effective in stories about issues that are controversial for political but not scientific reasons, such as evolution and climate change.

9. Obscure the methods and conclusions of the study as much as possible.

Try not to give many details about the study. A simplistic analogy is much better than actually describing the methodology. Better yet, don’t discuss the methods at all and simply focus on your own interpretation of the conclusions. Be sure to describe said conclusions in terms of absolutes, rather than the probabilistic or pluralistic ways in which scientists tend to summarize their own results. Error bars are not news.

10. Don’t provide any links to the original paper.

If possible, avoid providing any easy way for readers (in particular, scientists) to access the original peer-reviewed article on which your story is based. Some techniques to delay reading of the primary paper are to not provide the title or to have your press release come out months before the article is set to appear. An excellent example, which also combines many of the points above, is available here.

This list is not complete, but it should suffice as a rough guide to writing truly awful science news stories.