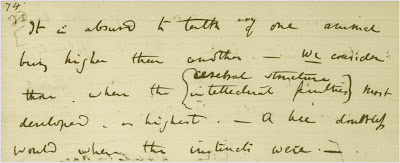

Charles Darwin (1809-1882) opened his first notebook about "the species question" in 1837, not long after his return from the voyage of the Beagle. By 1838, he had developed the basic outline

of his theory of natural selection to explain the evolution of species. He spent the next 20 years developing the theory and marshaling evidence in favour of both the fact that species are related through common descent and his particular theory to explain this. After receiving word that another naturalist, Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913), had independently come upon the same theory, he assembled his work for publication, first in a joint paper with Wallace presented to the Linnean Society of London in 1858 and then his "abstract", On the Origin of Species, in 1859.

of his theory of natural selection to explain the evolution of species. He spent the next 20 years developing the theory and marshaling evidence in favour of both the fact that species are related through common descent and his particular theory to explain this. After receiving word that another naturalist, Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913), had independently come upon the same theory, he assembled his work for publication, first in a joint paper with Wallace presented to the Linnean Society of London in 1858 and then his "abstract", On the Origin of Species, in 1859.

Some authors have argued that Edward Blyth (1810-1873), an acquaintance of Darwin's, developed the central idea of selection in an 1835 paper in the Magazine of Natural History. For example, Eiseley and Grote (1959) claimed that "the leading tenets of Darwin's work — the struggle for existence, variation, natural selection and sexual selection are all fully expressed in Blyth's 1835 paper", from which they then quoted the following:

It is a general law of nature for all creatures to propagate the like of themselves: and this extends even to the most trivial minutiæ, to the slightest individual peculiarities; and thus, among ourselves, we see a family likeness transmitted from generation to generation. When two animals are matched together, each remarkable for a certain given peculiarity, no matter how trivial, there is also a decided tendency in nature for that peculiarity to increase; and if the produce of these animals be set apart, and only those in which the same peculiarity is most apparent, be selected to breed from, the next generation will possess it in a still more remarkable degree; and so on, till at length the variety I designate a breed, is formed, which may be very unlike the original type.

It is a general law of nature for all creatures to propagate the like of themselves: and this extends even to the most trivial minutiæ, to the slightest individual peculiarities; and thus, among ourselves, we see a family likeness transmitted from generation to generation. When two animals are matched together, each remarkable for a certain given peculiarity, no matter how trivial, there is also a decided tendency in nature for that peculiarity to increase; and if the produce of these animals be set apart, and only those in which the same peculiarity is most apparent, be selected to breed from, the next generation will possess it in a still more remarkable degree; and so on, till at length the variety I designate a breed, is formed, which may be very unlike the original type.

As Eiseley and Grote (1959) and others have noted, however, Blyth's description applies to artificial selection, a process that had obviously been known to breeders long before. In terms of natural selection, Blyth suggested that it would be a conservative and not a creative process, acting to restore the original features modified by artificial selection; that is, it was not a process that caused change, but one that maintained stability within species. Neither Darwin nor Blyth considered this to have been an early example of Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection (see Schwartz 1974).

Patrick Matthew (1790-1874) did not feel the same way as Blyth, and was vocal in his belief that he had preceded Darwin as, according to calling cards he carried, "Discoverer of the Principle of Natural Selection". In fact, Matthew had proposed an idea similar to natural selection in his 1831 book On Naval Timber and Arboriculture,

There is a law universal in nature, tending to render every reproductive being the best possible suited to its condition that its kind, or organized matter, is susceptible of, which appears intended to model the physical and mental or instinctive powers to their highest perfection and to continue them so. This law sustains the lion in his strength, the hare in her swiftness, and the fox in his wiles. As nature, in all her modifications of life, has a power of increase far beyond what is needed to supply the place of what falls by Time's decay, those individuals who possess not the requisite strength, swiftness, hardihood, or cunning, fall prematurely without reproducing—either a prey to their natural devourers, or sinking under disease, generally induced by want of nourishment, their place being occupied by the more perfect of their own kind, who are pressing on the means of subsistence . . .

There is more beauty and unity of design in this continual balancing of life to circumstance, and greater conformity to those dispositions of nature which are manifest to us, than in total destruction and new creation . . . [The] progeny of the same parents, under great differences of circumstance, might, in several generations, even become distinct species, incapable of co-reproduction.

Darwin, like most others, was not aware of Matthew's book and he learned of it in 1860 when Matthew wrote a letter to the Gardners' Chronicle and Agricultural Gazette including excerpts from his book in response to a review of Darwin's On the Origin of Species.

In your Number of March 3d I observe a long quotation from the Times, stating that Mr. Darwin "professes to have discovered the existence and modus operandi of the natural law of selection," that is, "the power in nature which takes the place of man and performs a selection, sua sponte," in organic life. This discovery recently published as "the results of 20 years' investigation and reflection" by Mr. Darwin turns out to be what I published very fully and brought to apply practically to forestry in my work "Naval Timber and Arboriculture," published as far back as January 1, 1831, by Adam & Charles Black, Edinburgh, and Longman & Co., London, and reviewed in numerous periodicals, so as to have full publicity in the "Metropolitan Magazine," the "Quarterly Review," the "Gardeners' Magazine," by Loudon, who spoke of it as the book, and repeatedly in the "United Service Magazine" for 1831, &c. The following is an extract from this volume, which clearly proves a prior claim.

In a reply in the same magazine, Darwin said,

I freely acknowledge that Mr. Matthew has anticipated by many years the explanation which I have offered of the origin of species, under the name of natural selection. I think that no one will feel surprised that neither I, nor apparently any other naturalist, has heard of Mr. Matthew's views, considering how briefly they are given, and that they appeared in the Appendix to a work on Naval Timber and Arboriculture. I can do no more than offer my apologies to Mr. Matthew for my entire ignorance of his publication.

In terms of arguments that Matthew's contribution diminishes that of Darwin, I tend to agree with Peter Bowler, who said in his book Evolution: The History of an Idea,

Such efforts to denigrate Darwin misunderstand the whole point of the history of science: Matthew did suggest a basic idea of selection, but he did nothing to develop it; and he published it in the appendix to a book on the raising of trees for shipbuilding. No one took him seriously, and he played no role in the emergence of Darwinism. Simple priority is not enough to earn a thinker a place in the history of science: one has to develop the idea and convince others of its value to make a real contribution. Darwin's notebooks confirm that he drew no inspiration from Matthew or any of the other alleged precursors.

In any case, neither Blyth nor Matthew was the first to propose natural selection in very basic form. Another individual, an American physician of Scottish descent by the name of William Charles Wells (1757-1817), presented a paper in 1813 (published in 1818) that included a process of natural selection to account for differences in skin colour among people. Wells considered light skin to be the primitive condition, with dark skin a subsequent specialization.

Again, those who attend to the improvement of domestic animals, when they find individuals possessing, in a greater degree than common, qualities they desire, couple a male and female of these together, then take the best of their offspring as a new stock, and in this way proceed, till they approach as near the point in view, as the nature of things will permit. But, what is here done by art, seems to be done, with equal efficacy, though more slowly, by nature, in the formation of varieties of mankind, fitted for the country which they inhabit. Of the accidental varieties of man, which would occur amnog the first few and scattered inhabitants of the middle regions of Africa, some one would be better fitted than the others to bear the diseases of the country. This race would consequently multiply, while the others would decrease, not only from their inability to sustain the attacks of disease, but from their incapacity of contending with their more vigorous neighbours. The colour of this vigorous race I take for granted, from what has been already said, would be dark. But the same disposition to form varieties still existing, a darker and a darker race would in the course of time occur, and as the darkest would be the best fitted for the climate, this would at length become the most prevalent, if not the only race, in the particular country in which it had originated.

Darwin added an acknowledgment of Wells's work beginning with the 4th edition of the Origin in 1866,

In 1813 Dr. W.C. Wells read before the Royal Society 'An Account of a White Female, part of whose Skin resembles that of a Negro;' but his paper was not published until his famous 'Two Essays upon Dew and Single Vision' appeared in 1818. In this paper he distinctly recognises the principle of natural selection, and this is the first recognition which has been indicated; but he applies it only to the races of man, and to certain characters alone.

What Darwin (and until recently, most historians) did not realize was that the general notion of selection had already been proposed by 1794. In an review in Nature in 2003, Paul Pearson pointed out that James Hutton (1726-1797), considered the Father of Modern Geology, postulated something similar to natural selection in An Investigation of the Principles of Knowledge. (Pearson also noted the interesting bit of trivia that Hutton, Wells, Matthew, and Darwin all attended the University of Edinburgh).

As Hutton (1794) said,

…if an organised body is not in the situation and circumstances best adapted to its sustenance and propagation, then, in conceiving an indefinite variety among the individuals of that species, we must be assured, that, on the one hand, those which depart most from the best adapted constitution, will be most liable to perish, while, on the other hand, those organised bodies, which most approach to the best constitution for the present circumstances, will be best adapted to continue, in preserving themselves and multiplying the individuals of their race.

…if an organised body is not in the situation and circumstances best adapted to its sustenance and propagation, then, in conceiving an indefinite variety among the individuals of that species, we must be assured, that, on the one hand, those which depart most from the best adapted constitution, will be most liable to perish, while, on the other hand, those organised bodies, which most approach to the best constitution for the present circumstances, will be best adapted to continue, in preserving themselves and multiplying the individuals of their race.

…

Now, if those organised bodies shall thus multiply, in varying continually according to the particular circumstances in which are found the necessary conditions for their life and propagation, we might expect to see, in this world, a variety in the species of things, which we might term a race; varieties which do not affect the species of things, but which, upon many occasions, might appear to us as being a different race of the same species, whether of plant or animal. But, such things are every where observed; consequently, we have reason to conclude, it is truly in this manner, that are naturally produced those various races of plants and animals, which we find naturally upon the surface of this earth. Each of those races of things, therefore, would appear to us to be wisely calculated, by nature, for the purpose of this world.

Hutton used the examples of fast running and a strong sense of smell in dogs to illustrate the mechanism. He did not, however, accept the notion that new species could form by this or any process. For Hutton, this was limited to creating varieties only and not species.

It is important to note that Darwin himself recognized that others had discovered natural selection at least in basic outline before (and after) he had. He did not avoid sharing credit to the extent that it was due. In light of this history, one could argue that because natural selection as a mechanism had been proposed by several authors that it would have been discovered and recognized as important eventually, even without Darwin's input — and, indeed, it probably would have, as would Newton's laws of motion, Einstein's theory of relativity, and other fundamental principles describing the natural world. On the other hand, the idea had been around for at least six decades before Darwin published the Origin, and it was not until someone of Darwin's genius developed the idea that evolution assumed its position as the underlying theme of all biology.

_______

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to Genomicron feed.

of his theory of natural selection to explain the evolution of species. He spent the next 20 years developing the theory and marshaling evidence in favour of both the fact that species are related through common descent and his particular theory to explain this. After receiving word that another naturalist,

of his theory of natural selection to explain the evolution of species. He spent the next 20 years developing the theory and marshaling evidence in favour of both the fact that species are related through common descent and his particular theory to explain this. After receiving word that another naturalist,  It is a general law of nature for all creatures to propagate the like of themselves: and this extends even to the most trivial minutiæ, to the slightest individual peculiarities; and thus, among ourselves, we see a family likeness transmitted from generation to generation. When two animals are matched together, each remarkable for a certain given peculiarity, no matter how trivial, there is also a decided tendency in nature for that peculiarity to increase; and if the produce of these animals be set apart, and only those in which the same peculiarity is most apparent, be selected to breed from, the next generation will possess it in a still more remarkable degree; and so on, till at length the variety I designate a breed, is formed, which may be very unlike the original type.

It is a general law of nature for all creatures to propagate the like of themselves: and this extends even to the most trivial minutiæ, to the slightest individual peculiarities; and thus, among ourselves, we see a family likeness transmitted from generation to generation. When two animals are matched together, each remarkable for a certain given peculiarity, no matter how trivial, there is also a decided tendency in nature for that peculiarity to increase; and if the produce of these animals be set apart, and only those in which the same peculiarity is most apparent, be selected to breed from, the next generation will possess it in a still more remarkable degree; and so on, till at length the variety I designate a breed, is formed, which may be very unlike the original type.

…if an organised body is not in the situation and circumstances best adapted to its sustenance and propagation, then, in conceiving an indefinite variety among the individuals of that species, we must be assured, that, on the one hand, those which depart most from the best adapted constitution, will be most liable to perish, while, on the other hand, those organised bodies, which most approach to the best constitution for the present circumstances, will be best adapted to continue, in preserving themselves and multiplying the individuals of their race.

…if an organised body is not in the situation and circumstances best adapted to its sustenance and propagation, then, in conceiving an indefinite variety among the individuals of that species, we must be assured, that, on the one hand, those which depart most from the best adapted constitution, will be most liable to perish, while, on the other hand, those organised bodies, which most approach to the best constitution for the present circumstances, will be best adapted to continue, in preserving themselves and multiplying the individuals of their race.