I am not interested in engaging in debates with anti-evolutionists, though I am well aware of their key arguments. The big one, of course, is “irreducible complexity” — traits or features that supposedly could not have evolved because there is no conceivable function for their parts individually nor for a subset of their parts collectively. The bacterial flagellum apparently is the ultimate example of this, which explains why this microscopic protein “motor” can drive an entire philosophical argument along these lines.

I think Darwin said it best (as he often did) in 1871: “Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge; it is those who know little, and not those who know much, who so positively assert that this or that problem will never be solved by science.”

There is little concern among biologists that the evolution of bacterial flagella will be worked out, just as a tremendous amount of information is now available about the evolution of eyes (the previous Paleyan example of a supposedly un-evolvable structure).

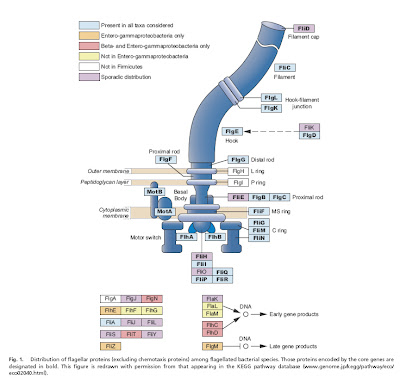

Last year, Pallen and Matzke (2006) presented a discussion of how bacterial flagella may have evolved, based in large part on comparisons of sequences from the various protein components. Many of the proteins that make up a flagellum have homologues that serve non-flagellar functions, strongly suggesting that they were co-opted from pre-existing proteins during the evolution of flagella. (See Matzke’s detailed model of flagellar evolution here and a video based on it here, and Ken Miller talking about flagella here). Specifically, there is ever-mounting evidence that bacterial flagella and the type III secretory system (TTSS) that toxic bacteria use to inject their prey are descended from the same ancestral structure. The fact that the TTSS lacks many of the proteins in flagella but remains functional (for toxin injection rather than locomotion) clearly indicates that not all the parts need to be present for some function to be carried out by the structure.

Pallen and Matzke (2006) noted that further comparisons of complete genome sequences (hence the post on this blog) would reveal additional insights into the evolution of flagella. Enter Liu and Ochman (2007) from the next issue of PNAS.

Liu and Ochman (2007) examined complete genome sequences from 41 species of bacteria with flagella, and were able to identify a core set of 24 proteins common to all of them, which was present in a very early ancestral bacterium. Not only this, but the core genes appear to be the product of multiple rounds of duplication and diversification, perhaps of one original precursor gene.

The gist of the story is that 1) some genes involved in the construction of flagella in modern bacteria are clearly co-opted from pre-existing genes that were doing something else in the cell (Pallen and Matzke 2006) and 2) a core of about two dozen genes common to all flagellated bacteria (and presumably found in their common ancestor) is the product of duplication and divergence whose reconstructed history agrees very well with the presumed evolutionary relationships among bacteria (Liu and Ochman 2007).

The gist of the story is that 1) some genes involved in the construction of flagella in modern bacteria are clearly co-opted from pre-existing genes that were doing something else in the cell (Pallen and Matzke 2006) and 2) a core of about two dozen genes common to all flagellated bacteria (and presumably found in their common ancestor) is the product of duplication and divergence whose reconstructed history agrees very well with the presumed evolutionary relationships among bacteria (Liu and Ochman 2007).

This just goes to show the usefulness of genome data for addressing questions that, for the reason outlined by Darwin, seem unanswerable to some. It also opens the door to some exciting future work.

I asked Howard Ochman what he thought the next key steps will be in this line of study. As he put it, “Naturally we would like to know the function of the structures that were specified by the ancestral set of flagellar genes, and how/why these genes remained functional through their successive duplications. We just completed a companion paper on the bacterial flagellar genes that arose later, and we are now branching out in into the other domains of life.”

I will positively assert, out of optimism rather than ignorance, that many more important insights will be forthcoming from these investigations.

(Update: Nick Matzke is very critical of the paper. He also has posted an updated critique that focuses more on the data.)

(Another update: See Carl Zimmer’s post about blogging as scientific debate).

(And yet another update: A complex tail, simply told at ScienceNOW)

_________

References

Aizawa, S.-I. 2001. Bacterial flagella and type III secretion systems. FEMS Microbiology Letters 202: 157-164.

Blocker, A., K. Komoriya, and S.-I. Aizawa. 2003. Type III secretion systems and bacterial flagella: insights into their function from structural similarities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 100: 3027-3030.

Gophna, U. , E.Z. Ron, and D. Graur. 2003. Bacterial type III secretion systems are ancient and evolved by multiple horizontal-transfer events. Gene 312: 151–163.

Liu, R. and H. Ochman. 2007. Stepwise formation of the bacterial flagellar system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 104: 7116-7121.

Matzke, N.J. 2003. Evolution in (Brownian) space: a model for the origin of the bacterial flagellum. Talk.Origins.

Miller, K.R. 2004. The flagellum unspun. In Debating Design: From Darwin to DNA, edited by W. Dembski and M. Ruse. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 81-97.

(available online here)

Musgrave, Ian. 2004. Evolution of the bacterial flagellum. In Why Intelligent Design Fails: A Scientific Critique of the New Creationism, edited by M. Young and T. Edis. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ.

(available online here)

Nguyen, L., I.T. Paulsen, J. Tchieu, C.J. Hueck, and M.H. Saier. 2000. Phylogenetic analyses of the constituents of Type III protein secretion systems. Journal of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology 2: 125–144.

Pallen, M.J., C.W. Penn, and R.R. Chaudhuri. 2005. Bacterial flagellar diversity in the post-genomic era. Trends in Microbiology 13: 143-149.

Pallen, M. J., S.A. Beatson, and C.M. Bailey. 2005. Bioinformatics, genomics and evolution of non-flagellar type-III secretion systems: a Darwinian perspective. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 29: 201–229.

Pallen, M.J. and N.J. Matzke. 2006. From The Origin of Species to the origin of bacterial flagella. Nature Reviews Microbiology 4: 784-790.