This year, Evolution: Education and Outreach will have a special (but not exclusive) focus on Darwin in celebration of the 200th anniversary of his birth and the 150th anniversary of the Origin of Species.

This year, Evolution: Education and Outreach will have a special (but not exclusive) focus on Darwin in celebration of the 200th anniversary of his birth and the 150th anniversary of the Origin of Species.

The first issue in volume 2 is now available, once again free online.

Evolution: Education and Outreach

Volume 2, Issue 1

Editorial: Darwin’s Year

Niles Eldredge and Gregory Eldredge

1

Why Darwin?

Niles Eldredge

2-4

Artificial Selection and Domestication: Modern Lessons from Darwin’s Enduring Analogy

T. Ryan Gregory

5-27

Charles Darwin and Human Evolution

Ian Tattersall

28-34

Experimenting with Transmutation: Darwin, the Beagle, and Evolution

Niles Eldredge

35-54

Studying Cultural Evolution at the Tips: Human Cross-cultural Ecology

Lauren W. McCall

55-62

Industrial Melanism in the Peppered Moth, Biston betularia: An Excellent Teaching Example of Darwinian Evolution in Action

Michael E. N. Majerus

63-74

Assessment of Biology Majors’ Versus Nonmajors’ Views on Evolution, Creationism, and Intelligent Design

Guillermo Paz-y-Miño C. and Avelina Espinosa

75-83

Darwin’s “Extreme†Imperfection?

Anastasia Thanukos

84-89

Don’t Call it “Darwinismâ€

Eugenie C. Scott and Glenn Branch

90-94

Educational Malpractice: The Impact of Including Creationism in High School Biology Courses

Randy Moore and Sehoya Cotner

95-100

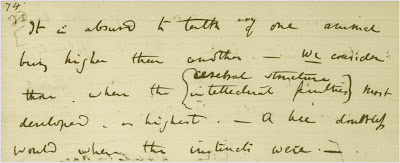

Scholar’s Dilemma: “Green Darwin†vs. “Paper Darwin,†An Interview with David Kohn

Mick Wycoff

101-106

The “Popular Press†Responds to Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species and His Other Works

Sidney Horenstein

107-116

Paleontology and Evolution in the News

Sidney Horenstein

117-121

Charles Darwin’s Manuscripts and Publications on the World Wide Web

Adam M. Goldstein

122-135

Teaching Evolution in Primary Schools: An Example in French Classrooms

Bruno Chanet and François Lusignan

136-140

Why Why Darwin Matters Matters

Why Darwin Matters: The Case Against Intelligent Design, by Michael Shermer. New York: Henry Holt, 2006.

Tania Lombrozo

141-143

DeSalle’s and Tattersall’s Human Origins: A Companion to The Museum of Natural History’s Hall of Human Origins and More

Human Origins: What Bones and Genomes Tell Us about Ourselves, by Rob DeSalle and Ian Tattersall. College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 2008. Pp. 216. H/b $ 29.95

Robert Wald Sussman

144-147

I am not certain whether the dedication we wrote to the late Dr. Majerus will appear online, but I am hoping it will be included in the print issue. Here it is, just in case.

This issue of Evolution: Education and Outreach includes a paper by Prof. Michael Majerus of Cambridge University, a world expert on industrial melanism and a champion of the peppered moth as an excellent example of natural selection in the wild. In it, Prof. Majerus describes the controversy surrounding the peppered moth, much of it based on misrepresentations and misunderstandings. He also describes, with extraordinary modesty, his own widely respected research which has refuted the misplaced criticism of the peppered moth example.

We consider the paper a testament to Prof. Majerus’s patience and dedication to settling debates in science as they should be settled – with evidence rather than rhetoric. In this regard, Prof. Majerus’s paper not only highlights an exquisite example of evolution in action, but also serves to illustrate how careful scientific study generates outstanding results.

It is with deep regret that we note that Prof. Majerus passed away peacefully during the night of January 26/27 from a brief but severe illness. As Prof. David Summers, Head of the Department of Genetics at Cambridge, wrote

“Mike Majerus was a traditional Cambridge scientist; a charismatic individual for whom the boundaries between life and work, and teaching and research, were very hard to discern. He was a world authority in his field, a tireless advocate of evolution and an enthusiastic educator of graduate and undergraduate students.”

We are proud to present Prof. Majerus’s article on the peppered moth and are grateful for his contribution to the journal, for his important and diligent research, and for his dedication to defending and enhancing science education. We extend our deepest condolences to his family, friends, and colleagues. He will be missed.

T. Ryan Gregory

Associate EditorNiles Eldredge

Editor-in-Chief